Floor inlay map, Finger Lakes Welcome Center, Geneva, NY

I’ve been in love with New York’s Finger Lakes region pretty much ever since we moved to New York in 1981. My first sight of any of those lakes came that first summer. We moved here in June, I think–pretty quickly after I completed fourth grade in Hillsboro, OR–and when we got here my mother had to do a bit of coursework to fulfill the requirements for her new teaching job in this state. This meant trekking from Allegany to Geneseo, NY, mostly every day for the summer. Sometimes my sister and I would stay home, other times we’d go along; and while Mom was in class, Dad and I would go off exploring.

Nowadays, whenever The Wife and I drive eastward into the Finger Lakes region, when we arrive in Geneseo via US 20A, I always consider that little college town to be the western “gateway” to the Finger Lakes region. Just east of Geneseo lies Conesus Lake, the westernmost of the eleven Finger Lakes. It’s also one of the smallest, but that was the first one I saw, way back when. Nearby are undeveloped Hemlock and Canadice Lakes, left undisturbed because they are sources of drinking water for the Rochester urban area 30 miles north. Then there is Honeoye (pronounced “Honey Eye”), which is another very small and highly developed lake with cottages and whatnot all around. Then you’re into the central Finger Lakes, where the big ones lie: Canandaigua (near the shores of which is the 4H Camp that housed the summer music camp I attended several years and then worked at several more as a counselor), Keuka (with its unique Y-shape), and the two biggies, Seneca and Cayuga (biggest and second-biggest, respectively).

The central lakes are big enough that they famously create their own microclimate in their long, narrow valleys, a microclimate that is ideal for the growing of wine grapes: hence New York’s excellent wine production. At the southern end of Cayuga Lake is my beloved dream hometown of Ithaca, while at the northern end of Seneca lies another town we love, Geneva. Around these lakes lie many other wonderful places: Watkins Glen, Seneca Falls, Aurora, Trumansville, Taughannock Falls, and more.

The Finger Lakes were a no-brainer for a location when I was thinking about booking a getaway for The Wife and I on our 25th anniversary (now several weeks back).

After doing some searching, I booked a cottage in Watkins Glen, directly overlooking the lake itself, and then while there, we used that cottage as a base for some exploring. We went to Ithaca for a day to see things that we usually don’t see because we always go to Ithaca in the fall for the Apple Harvest Festival, and then the next day we drove south to Corning to visit the Museum of Glass, a world-class attraction that I have spent the better part of the last 41 years within a two or three hour drive and yet never been. And also, we ate pretty damned well, too.

I have an entire album on Flickr of pictures I took from that trip (though I haven’t gone through yet and captioned many), but I’ll run some favorites below.

Seneca Lake from Fulkerson Winery

Wine tasting. We bought six bottles here at the start of our trip. We came home with two.

Seneca Lake, looking north from the dock at our cottage property.

To get to the dock you have to walk across a street, down a flight of wooden stairs, then across these tracks (which are still in use as there is a literal salt mine a mile up the lake). Not an impediment in any way! In fact, this made the place feel even more old-school and rustic, in a way.

A pretentious pose. If I ever do an acoustic indie-rock album (and I will not, mind you) this might be my cover art. OR, this could be the photo that accompanies a news magazine profile of the grizzled guy who watches the time go by from the shores of his beloved lake….

I love when you can see far enough and it’s just cloudy enough that you can see sunny patches on the distant hills.

Looking toward the village of Watkins Glen. It was still too early for there to be a lot of boats out yet; I imagine that starts up in earnest on Memorial Day Weekend. Note the passing rain clouds in the valleys to the south. I had issues, growing up in New York’s Southern Tier, but those forested hills are really something special.

Morning reading, before The Wife got up.

There is a LOT of public art in Ithaca.

The Chanticleer in Ithaca. I love their sign and I photograph it anew almost every time we’re there. Never been inside (it’s a bar).

Chicken and waffles at Waffle Frolic. We ADORE this place. We tried going last fall, but we missed them by half an hour, not having realized that their pandemic hours had them closing at 1pm! We were NOT going to fail THIS time. The orange sauce is their maple hot sauce; the other one is maple syrup. And YES, you use BOTH. I could eat this weekly.

The Odyssey Bookstore is one of Ithaca’s newest bookstores, having opened in 2020, just as the pandemic was starting up. Ouch, that timing…but they appear to be going strong! It’s a lovely little place in the basement of an old house, just beautiful for browsing. We only stopped in one bookstore this trip. I had to control myself SOMEHOW.

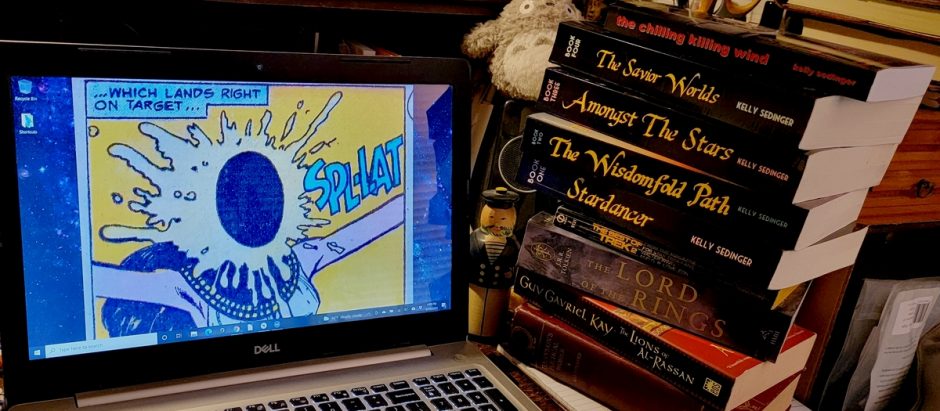

My book haul from Odyssey. Yes, for me this is “self-control”.

The “waterfront” at the Ithaca Farmers Market. We’d never been to this market, and it was wonderful! Everything a farmers market SHOULD be. (Among other things? Multiple people wearing overalls! I always feel like I’m amongst my people when I’m in Ithaca.)

Cayuga Lake, looking north from the top floor of the Herbert F. Johnson Art Museum in Ithaca (at Cornell). Wonderful views from up there. (And great art! Check the Flickr album for some of that.)

Ithaca, from the top floor of the Herbert F. Johnson Art Museum (Cornell). What a beautiful city Ithaca is. I could move there TOMORROW. (Well, next week. I’d need time to pack.) I only recall going to Ithaca a few times as a kid…with all the road-tripping we did, I wonder why Ithaca wasn’t a destination more often….

On Day Three we had breakfast at this butcher shop-and-eatery in Corning. Fantastic. We’d been planning to pick up something to grill (our cottage came with a grill) at the local grocery store in Corning, but we ended up buying two thick pork chops from here instead. Loved it.

Several items from the Corning Museum of Glass. More in the Flickr album. (MANY more. I took a LOT of photos that day. This museum is fantastic. We spent hours there and didn’t even see everything!)

Apparently in 1972 the Chemung River flooded BADLY in Corning and environs, resulting in considerable damage to the Museum of Glass. The Museum is only about a thousand feet from the river. This must have been devastating.

Another sun-dappled hill.

This fascinated me. It’s across the side-street from the ice cream place we visited in Watkins Glen. I wondered about that steep garage-door ramp thing. It turns out that this is the access entrance for cars to be driven up into, and out of, the upstairs showroom of the REALLY old-school car dealership which is in downtown Watkins Glen. The building still is a car dealership, though the upstairs showroom isn’t in use for that purpose anymore. Watkins Glen’s long automotive history is still apparent!

Two views from our last night there.

A stop on the way home at the Rasta Ranch Winery, a favorite of ours. The place is 60s-themed, very Woodstock. More wine bought here. (We were unable to stop during our wine tour back in February.)

From the Rasta Ranch (on the east shore of Seneca Lake) we could see the rain clouds approaching from the west. The day ended up being pretty much of a washout. We’d planned on a slow sight-seeing kind of drive home; that didn’t happen, sadly. Alas! A lovely weekend, though.

Pouring rain at Geneva. This is the northern shore of Seneca Lake, looking south; usually you can see for quite a distance. Not so THAT day. We’ll be back, though!

The whole Finger Lakes region isn’t just beautiful, with forests and high hills and deep valleys and waterfalls and streams and wineries and those gorgeous lakes, but it’s also by its very rugged nature something of a land that time forgot. The very geography and geology team up to make the entire region pretty much impervious to that enemy of all such onetime resort meccas, the four-lane highway. You can pretty much speed past the entire region to the north (via I-90) or the south (via I-86) in about 90 minutes, or you can get off the infernal expressways and take the twisting two-lane roads that run along high ridges before plunging into lake-filled valleys. You’ll drive past old places that were once bustling stops along the railroads that aren’t so bustling anymore, but the places endure, somehow.

I can’t wait to go back.

I miss our old futurists

UPDATED below.

I saw these two tweets the other day, in reaction to Elon Musk’s widely publicized dictum that his employees have to put in their 40 hours a week at the office, no ifs ands or buts, no refunds returns or exchanges, that’s just the way it is, because something something gazpacho:

https://twitter.com/LouisatheLast/status/1532791845322883073

https://twitter.com/LouisatheLast/status/1532792510015320067

I like it when someone comes along and succinctly says something that I’ve been struggling to crystalize in my own mind. Elon Musk is largely feted because he’s apparently a vanguard of our wonderful future…or, at least, that’s the pleasant veneer that has been applied to him. But when you really get down to it, that’s not at all what he is. He’s just a rich capitalist with a shiny thing to sell. That’s it. That’s all he is, all he ever was. He stands on the shoulders of giants and with his piles of money convinces millions that he got there by virtue of some special genius unique to him.

But then he says stuff about his businesses and how he wants his employees to behave and be forced to work, and you get a glimpse under the hood. And you realize there’s nothing new there at all: he’s nothing more than a railroad tycoon, maintaining absolute control over his giant well-moneyed empire.

Elon Musk is no futurist. He has said nothing about improving the human condition in any way other than the same old idea that rich people should just be allowed to keep doing rich people things, that humanity is best served by letting rich people prosper and that their underlings should be happy to work, work, work for the greater glory of The Company and the CEO.

Elon Musk’s future is pretty much the same as the world we’re in now, only with different insignias in chrome on the backs of the cars. It’s a world where the pursuit of wealth is the paramount human concern, where the entire economy is propped up on the illusion of work as the paramount function of the individual, where life must be earned through work. There is nothing new under the sun in Elon Musk’s worldview. Nothing at all.

We need better futurists.

UPDATE: I wrote this post yesterday and scheduled it for this morning. Then, I see this:

The way Elon Musk wildly vacillates between “Rich Capitalist Overlord Who Demands Loyalty And Labor From His Underlings” and “Aging Stoner Using Star Trek Action Figures To Play-act His Future Visio” really ought to give more of us pause….