Hello, all! Time for another post on characters and how to approach them…or how I approach them…or, in this case, how another writer approached them.

So let’s talk about Calvin and Hobbes.

This legendary comic strip is still well known today, despite that fact that its creator, Bill Watterson, ended it nearly twenty years ago (in fact, this coming December 31 will mark the 20th anniversary of the final strip of Calvin and Hobbes). Watterson created a bunch of interesting and memorable characters, and at the center of it all was six-year-old Calvin and his beloved stuffed tiger, who in Calvin’s presence (and only in Calvin’s presence) was a living, breathing being.

Calvin was not very well-behaved. He wasn’t focused in school, he engaged in all manner of shenanigans that got him in trouble constantly, and he wasn’t terribly nice to the little girl down the street. In these particulars, he probably wasn’t all that different from a lot of six-year-old little boys, and while it’s tempting to read into Calvin’s psychology (and yes, you can find a lot of such commentary online), it’s best to realize that it’s all fiction and that Calvin likely is the star of a comedy strip, and not a real kid desperately in need of a truckload of Ritalin.

Watterson does not depict Calvin solely by his negative qualities, though, and it’s telling that those negative qualities seem to only come out when Calvin is forced to engage with other people. Ultimately Calvin is something of a loner, and when he’s allowed to do his own thing, he is depicted as an amazingly creative and imaginative little boy. Mostly this drives everyone around him to distraction, but occasionally people notice that it’s a good thing. There’s one strip that has Calvin imagining that he is A GOD, creating a world out of nothing…and then we cut to his parents in the last panel. Dad says, “Have you seen how absorbed Calvin is with those Tinkertoys? He’s making whole worlds in there!” And his Mom replies, “I’ll bet he grows up to be an architect.” (Of course, they don’t know that Calvin is imagining wreaking his evil vengeance upon the world as a God of the Underworld, but what they won’t know won’t hurt them.)

I read an article some months ago — which I didn’t bookmark and now I can’t find to save my life — that seemed to argue, if I recall correctly, that Watterson erred in ending an early story arc in the C&H run. This arc had Calvin’s Uncle Max (his father’s brother) come to visit, during which time he stuck around and made some commentary on Calvin’s tendency to being a loner and attachment to an “imaginary” friend and so on. The article argued (and again, I may have this very wrong) that Uncle Max represented an opportunity to show Calvin’s continued “growth” in some way. Watterson, on the other hand, recognized Max as a storytelling mistake. In his Tenth Anniversary book, Watterson wrote this about Uncle Max:

I regret introducing Uncle Max into the strip. At the time, I thought a new character related to the family would open up story possibilities: the family could go visit Max, and so on. After the story ran, I realized that I hadn’t established much identity for Max, and that he didn’t bring out anything new in Calvin. The character, I concluded, was redundant. It was also very awkward that Max could not address Calvin’s parents by name, and this should have tipped me off that the strip was not designed for the parents to have outside adult relationships. Max is gone.

That’s pretty insightful. A good character isn’t a good character in and of him or herself. A good character isn’t just well-developed and realistic and memorable and all those other things. A good character must serve the story and fit into the story’s world and tone. A character who doesn’t do those things is not a good character. Unfortunately for Watterson, he realized his error with Uncle Max after the character had already appeared in print, so he couldn’t just strike him from the record, could he? So now, Uncle Max is a real thing, complete with fan speculations and whatnot. (Someone out there has a pet theory that Uncle Max and “Lyman”, a disappeared-character of similar appearance from Garfield, are the same person. I am not making that up, either.)

Max doesn’t fit in the Calvin and Hobbes universe because about the only thing he can offer in terms of storytelling possibilities is a new setting for Calvin’s adventures as a loner, and that’s a pretty lame reason to have yet another outside person to be flummoxed by Calvin’s oddities. The person arguing that Max could have been a key, in some way, to Calvin maturing over time was missing a very huge point.

However, something else interesting happened as the strip neared its conclusion. Watterson eventually did allow a single outside character, and only one outside character, into Calvin’s world. He did this on an extremely limited basis (this character did not suddenly see Hobbes as a real tiger), but this storyline — one of my favorites in the entire run — was the only time I can remember an outside person interacting with Calvin on Calvin’s terms. That person was Rosalyn, Calvin’s embattled babysitter.

Rosalyn was a recurring character whose appearance on the scene always meant funny things were afoot. Her story arcs would run over the course of several days as each time Calvin did something else to get in trouble, make Rosalyn’s night miserable, and amuse the readers with all manner of hijinks. Rosalyn was also smart as a whip; having recognized the inherent lucrative nature of being the only neighborhood babysitter willing to supervise Calvin, she priced her services accordingly, much to the chagrin of Calvin’s dad, who knew that he was getting taken advantage of and could literally do nothing about it.

The last time Rosalyn showed up, the story started in pretty typical fashion. We know what’s going to happen: Rosalyn is going to threaten Calvin with doom if he misbehaves, and he’s going to misbehave anyway, and the night is doomed.

However, things go slightly differently, as Rosalyn has a different plan:

Calvin actually meets his end of this bargain (and God bless Watterson’s memory of how big an incentive it can be for a kid, being allowed to stay up late, even just half an hour), and Rosalyn meets hers: allowing Calvin to pick his favorite game to play. Now, she is undoubtedly expecting him to pick Sorry! or Monopoly or some such board game, but of course, Calvin picks Calvinball.

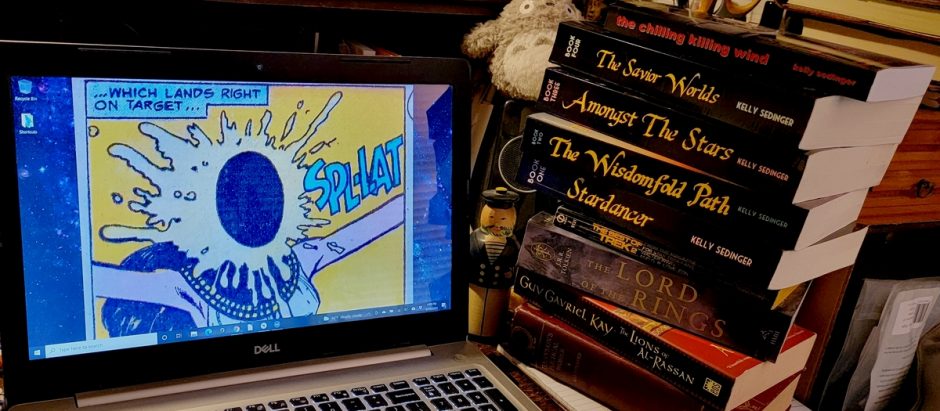

Calvinball, for those possibly unfamiliar with the strip, is a game whose one and only rule is the rules are never the same each time out. Rosalyn, of course, has absolutely no idea what to expect, but into the game she goes, quickly picking up the “rules”:

Rosalyn is actually engaging Calvin on his own terms here, and again, as far as I can recall this is the only time this happens with any outside person at all in the history of the strip. It’s really quite fascinating, since by its nature, Calvin and Hobbes is really fairly static in terms of character development for its entire run. Yes, we see different aspects of Calvin’s character over the years, but he never really changes, and that’s as much a necessity of the medium as anything else. (How much did Charlie Brown or Lucy ever change? Or Dagwood? Or Garfield? Or….) But here, we see definite change in one key way: Calvin finds a way (without looking) to connect with Rosalyn, and she finds a way to connect with him. As this story progresses, the water balloon is there, ready to be thrown at someone, and I remember thinking at the time that the water balloon was going to the source of Calvin getting in trouble this time, but then Rosalyn uses the “rules” of Calvinball to her advantage:

There’s a wonderful coda to this storyline when Calvin’s parents get home and ask how things went, and Rosalyn says something like “Fine! Calvin did his homework, we played a game, and he went to bed,” to which Dad replies, “I’m in no mood for jokes!” He’s utterly convinced, you see, that this night will be like all the others and he’s coming home to an angry babysitter and his misbehaving kid.

(By the way, if you want to read this entire storyline — I don’t include each installment here — start here and click forward. There’s a Sunday strip in there that does not pertain to the Rosalyn storyline.)

Now, is Rosalyn a great character? Not particularly, because like everyone else, we only get to see her through the prism of Calvin and his reactions to her, but she does make possible some great moments along the way. Watterson wisely used her sparingly, noting that each time she showed up there was a sense that he had to outdo himself. With this story, Rosalyn does something no one else has done: she has entered Calvin’s world. It’s telling that this was the last time Rosalyn appeared before the strip ended. I don’t know if Bill Watterson wanted to have someone pull off this feat before he wrapped things up, but for my money, Rosalyn was really the only character who could have done this. For one thing, it’s completely unexpected, but for another, it’s done in the perfect way.

One last observation on this: Watterson also wisely knew what he could do with his characters when. This is important. He couldn’t have this story be the first one when Rosalyn showed up, because then there would be an underlying sympathy for her every time thereafter. This story could only be the last Rosalyn story. Likewise, the James Bond stories can’t start with On Her Majesty’s Secret Service, and Macbeth can’t start with Macbeth having usurped the throne, and so on. The audience has to be prepared to go where the characters are going, and if the characters go there before the audience is — or even can be — ready, then the story is going to feel forced and false.

And with that, I’ll have done. Thanks for hanging in there, and hey! Over the next few weeks, I’ll start dripping out some real concrete information and teaser stuff pertaining to The Wisdomfold Path! November 10 is coming, folks!