Greetings, Programs!

The other day, the ever-fantastic Briana Mae Morgan asked on Twitter:

I am simultaneously excited and nervous to be writing a series. It’s my first series! How do y’all do this?

— briana morgan PREORDER LIVINGSTON GIRLS! (@brimorganbooks) January 5, 2020

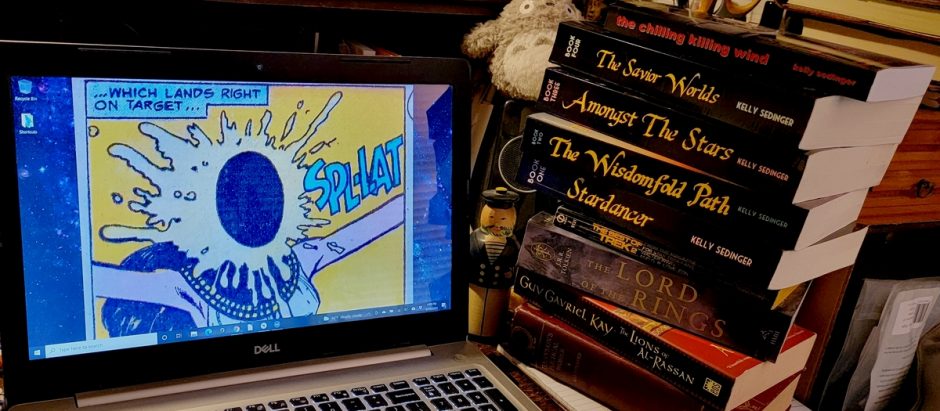

Naturally, I responded, because I have committed or am in the process of committing several crimes of Serial Fiction, and now I’m going to extend my thoughts a bit as to how to write a series.

I tend to think of storytelling, at its most basic, in terms of structure, so naturally my thoughts on writing a series would turn to structure. That means that if you’re considering committing an act of series, you have to ask yourself this question first:

What kind of series am I writing?

The answer to this question will affect how you write your series. So, what kind of series are there? The options, as I see them, are these:

TYPE 1. A single-story series, told serially.

Examples here are many of the long fantasy series out there: The Wheel of Time, The Belgariad, The Expanse, and A Song of Ice and Fire are good examples. Each book tells a part of the larger story, and reading the books out of order can be disorienting or downright confusing for readers who are jumping into the middle of the story.

At first glance, The Lord of the Rings might be thought an example of this, but I don’t think it is. LOTR is better thought of as a single huge book that for publishing reasons was broken down into a trilogy. There is no functional break between The Fellowship of the Ring and The Two Towers and The Return of the King, and each volume is only a part of the larger whole.

I would also file the Harry Potter books here, but they’re a bit of a special case in that each book tells a piece of the larger story while also serving as a self-contained unit. The later volumes have less stand-alone appeal than the earlier ones, but they still have internal structure. Can you read them in any order? Not really–but there’s enough internal structure to each book that it wouldn’t be as disorienting as trying to jump into A Song of Ice and Fire with A Feast for Crows.

TYPE 2. An open-ended series with larger story elements, but not a single larger story.

In a series like this, each novel is mostly independent, but there is character development and larger story development along the way. Events of earlier books have impact on the later ones, but there’s generally less danger in starting such a series somewhere in the middle. The James Bond books are a good example here, or Lois McMaster Bujold’s Miles Vorkosigan books.

TYPE 3. A series of independent stories featuring a starring character or a group of characters.

With this kind of series you can start at any point, because the books (or movies) are for the most part completely unrelated and self-contained from one to the next. The James Bond movies apply here (Ian Fleming’s books have more continuity than the movies, at least up until the Daniel Craig era, which have more continuity than any other sequence of Bond films to date), as do Agatha Christie’s Miss Marple and Hercule Poirot books. I’m not sure if Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes stories work under this definition.

So, once you know what kind of series you have on your hands as a writer, your next course becomes clear. If you’re writing that last kind, you’re golden because you don’t have to do any planning of any kind beyond what you would plan for a single novel. Just finish the current adventure or story, and then move on to the next one. Lather, rinse, repeat for as long as you’re comfortable tracking the adventures of a single character.

Now, with a series like that, you might want to have some continuity as you go: recurring villains, perhaps. Holmes had his Moriarty and Bond his Blofeld, after all. But you don’t have to do that: I don’t recall that John Bellairs had Lewis Barnavelt or Johnny Dixon square off against the same dastardly supernatural baddie more than once (though I may be wrong).

It seems to me that the difficulties with series writing creep in with a Type One or a Type Two series. With these types of series, more planning is needed.

With a Type Two series, in which there are ongoing serial elements but no real larger “story”, a degree of planning is still needed for two reasons. First, all installments must reflect what has come before. If you shatter your protagonist’s heart at the end of one installment, you can’t have them bounce right back into a new relationship in the next. You have to be able to accommodate the changes in your characters over time, and what’s more, you have to let them change over time. In a Type Two series, your character can’t be the same person in the tenth installment that they are in the first.

Second, while leaving room for surprise and discovery is great, you’re better served if you know beforehand what kind of larger arc your characters or your story are going to follow. You need to have at least a partial idea of how you expect your characters to change and grow and what kinds of things are going to change in their world. A series of stories following, say, a sword-wielding warrior for hire as she journeys through various kingdoms and realms, should see the world change as she roams through it. Wars begin, perhaps; or maybe the cities are visited by plagues…whatever. The world should change, and your character should change along with it. And if that happens, you should have a bit of an idea of what kinds of changes might happen.

(Again, none of this should rule out the serendipity of a sudden burst of insightful inspiration that leads you to do something you hadn’t expected!)

This leaves us with the Type One series: the series that tells a single story, beginning to end, but writ large over the course of several individual stories or books. For one of these, you’d better do some planning, or you’ll end up really bogged down once you’re in the thick of it.

The bigger a story is, the more moving parts it has, and these all have to work together. Your cast of characters is likely much larger if you have a big story to tell, and they all have to develop along the way and their actions and choices have to affect the story, or else it feels like the characters are just cogs in a big machine of plot. But here’s the thing: with a big series it can likely be very tempting to just start out and figure out the big plot later, but if you do this, pitfalls await.

Your early books might not end up sufficiently supporting or establishing the larger plot to follow, or crucial things about your characters. If you find yourself needing Mary in Book Four to have a very specific talent that requires years of training to master, and you’ve never hinted in Books One through Three that she has this talent, it can be jarring for the reader or eject them outright from your book.

More importantly, telling a very large story without planning can lead you to losing the story entirely. You can find yourself wandering down tangents, or finding that farther on down the line your entire notion of how the story works has changed, or you might change your mind as to what happens. On the other hand, though, as with any story I feel strongly that outlines or plans should not be constrictive to the point of being a straitjacket, crushing spontaneity. You never know when the next great idea is going to come along, but if you’ve done the groundwork for your series, the great ideas are likely to supplement the work rather than supplant it.

So, those are my thoughts on writing series. Of course, my thoughts might change as I get farther into my own respective series!

Thoughts?

See you ’round the Galaxy,

-K.

Pingback: Plannie McPlannerson - Forgotten Stars.net